Case of the Month - July 2024

Consult

55 year old patient who presented after MVC with deep penetrating neck and chest injuries requiring surgical exploration of the left chest and base of the neck. One week after surgery he continues to have >1L of chylous output from the surgical drains, concerning for injury to the lymphovenous junction/thoracic duct.

Lymphatic anatomy is variable but classically the thoracic duct drains into the systemic veins near the junction of the left internal jugular and subclavian veins (overview of lymphatic anatomy). Trauma and surgery are the most common causes of lymphatic leaks and chylothorax.

Fluid studies with >110 mg/dL triglycerides, >200 mg/dL cholesterol, or detection of chylomicrons are diagnostic of chylous fluid.

You decide to perform a lymphangiogram. Common options for access include pedal and intranodal.

Traditionally, pedal access was used. Now intranodal access is most common for efficiency. Other described approaches include transvenous retrograde access or direct puncture of the lymphovenous junction under ultrasound guidance.

Bilateral inguinal lymph nodes were accessed with 25G Whitacre spinal needles via a long lateral subcutaneous approach for needle stability. Lipiodol (Guerbet) was injected slowly (0.1-0.3 mL/min) with intermittent fluoroscopic monitoring.

Sequential compression devices were placed prior to the procedure to increase lymphatic flow and decrease procedure time.

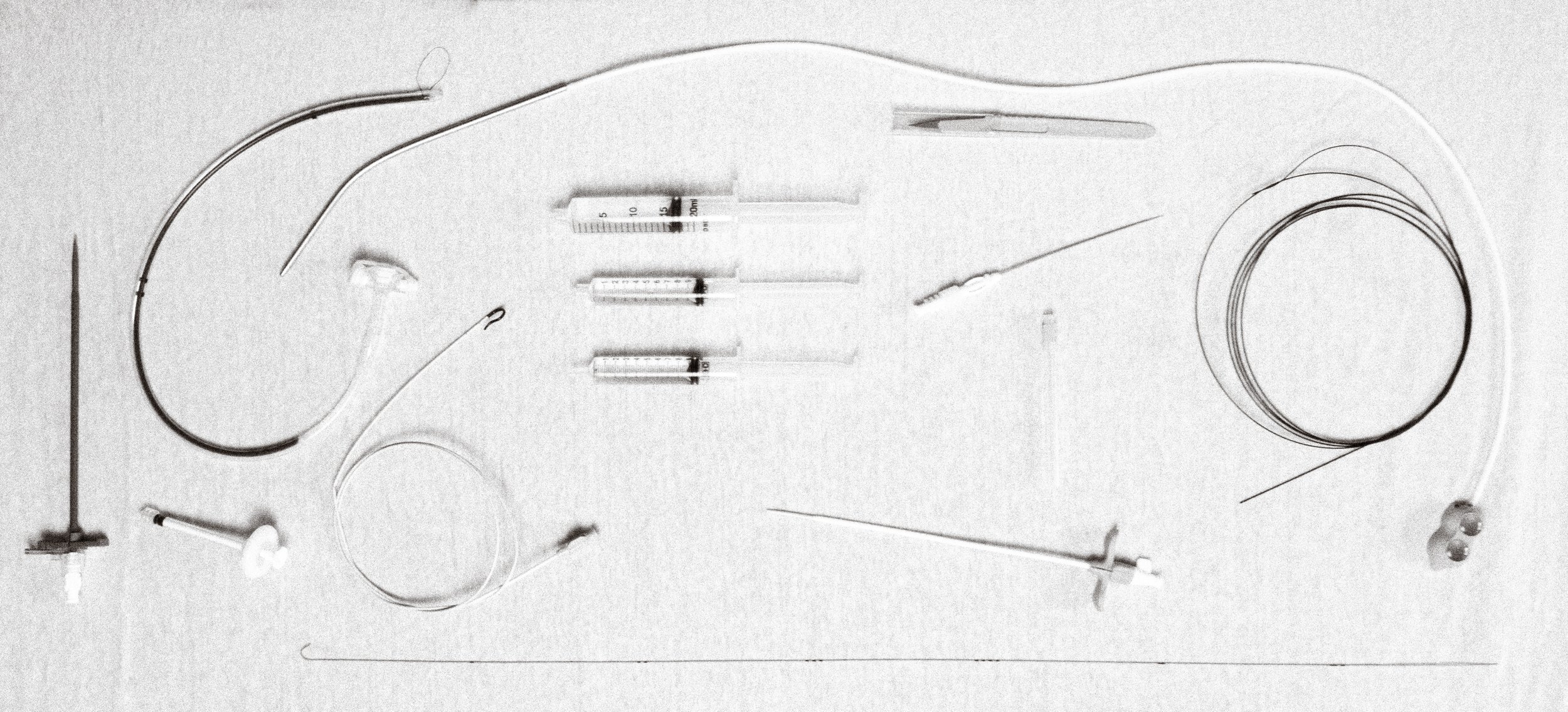

Lymphangiogram confirmed suspected injury of the lymphovenous junction with leak. The cistera chyli was identified at the level of L1 and accessed under fluoroscopic guidance with a 22G chiba needle and 0.018 in. Nitrex wire (Medtronic).

Lymphatic leak treatment options include conservative management, disruption, embolization, and surgery. Conservative management is often trialed first consisting of low fat diet or remaining NPO with TPN with octreotide drip. However, this is only successful in approximately a third of high volume lymphatic leaks.

Lymphangiography alone with lipiodol can lead to clinical improvement in up to 60% of patients, particularly if no leak is identified or the leak is inaccessible.

Percutaneous disruption of the culprit duct or injection of a liquid embolic (e.g. glue) via an adjacent node can be successful if unable to cannulate the culprit duct.

Otherwise, thoracic duct embolization tends to be >80% clinically successful across studies. Outcomes are superior if a liquid embolic such as glue is used with or without coils compared to coils alone.

Surgical ligation is another option though has significantly higher risks. As such, it is often reserved for cases refractory to minimally invasive interventions.

Thoracic duct embolization was performed using microcoils and LAVA (SIRTEX). The leak resolved and the drains were removed a few days after the procedure.